It’s 2 a.m. and darkness looms over the base. Offices are deserted and the streets are quiet, but out on the runway a single light cart glows, cutting through the thick fog and mist.

Under the light, members of the 786th Civil Engineer Squadron barrier maintenance team move frantically back and forth along the runway. They are there to ensure the “BAK-12/14” aircraft arresting system is ready to safely engage aircraft in case of an in-flight emergency.

Led by Tech. Sgt. Franklin Furman, 786th CES barrier maintenance NCOIC, the team would normally prefer working during the day, but one night a month they ensure the $250,000 system is properly maintained.

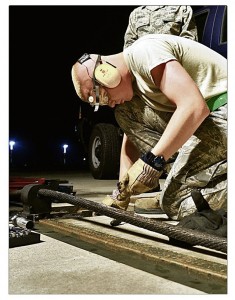

Airman 1st Class Jonathon Moore, 786th CES electrical power production technician, replaces the cams and torsion springs in the BAK 14 support box Dec. 1 on Ramstein. This project was important because many of the parts only have a certain time that they can be in operation before they have to be tested and replaced to ensure the systems in-flight emergencies can be safely grounded, saving a pilot’s life and billions of dollars worth of aircraft.

“We get one eight-hour window every month where the main runway is closed for us to perform all of our maintenance checks and do any quick fixes,” Furman said. “That time is vital for us to be able to do our job without constantly worrying about incoming aircraft forcing us off the runway.”

To ensure 100 percent coverage in any weather condition, each end of the main runway has a BAK-12/14, which rests just below the concrete surface. The system is hardly visible to the naked eye, but when a distressed aircraft is on approach, the BAK-12/14’s 1.25-inch diameter steel cable appears above the runway surface.

The 1.5 inch height of the cable is critical because of the tail hook on the incoming aircraft. If the cable is not high enough the hook could miss the cable and cause catastrophic damage to the aircraft, and possibly endanger the life of the pilot.

“This project was important because many of the parts only have a certain time that they can be in operation for a certain length of time before they have to be tested and replaced, to ensure in-flight emergencies can be safely grounded, saving a pilot’s life and billions of dollars worth of aircraft,” said Airman 1st Class Jonathon Moore, 786th CES electrical power production technician.

There are a total of 28 solid steel boxes comprising the two BAK 14s. In each box, there are a series of pins, springs, pulleys, and a pneumatic piston, which raise and lower the 800 pound cable into place.

“My role in this project was to replace the torsion springs and the cams in the BAK 14 support box to ensure the cable will continuously be able to rise above and go back under the runway when not in use,” Moore said.

The system runs on compressed air to lower and hold the cable in the down position. In the event of an emergency, the system is remotely activated from the Air Traffic Control Tower. When engaged, a sensor switches off the compressed air in the steel boxes, and a torsion spring mechanically lifts the rubber cable support blocks above the runway surface.

Only then does the BAK-14 display its taut steel cable, which is strung across the runway at a static pressure of 175 psi. When engaged, two underground arresting motors use a massive tape wheel and hydraulic pressure to put the brakes on the cable.

“It works much like a retractable dog leash; except, instead of Fido chasing a nearby squirrel, this leash can halt a 40-ton aircraft traveling at speeds up to 180 nautical miles per hour in a split second,” Furman said.

Recently, the Barrier Maintenance team completed the 10-year overhaul of the BAK 14. This task, which took about four months to complete, comprised of replacing 28 support arms, 56 torsion springs, 28 rubber support blocks, 56 cams, 112 cam bolts, 56 wire spokes, 112 2-inch cotter pins, and 112 small springs.

“Imagine spending hours on your hands and knees in the middle of the cold concrete runway; wrestling with heavy, greasy and awkward parts in a space that a child would have trouble slipping their fingers into,” Furman said. “It’s like trying to put 10 pounds of potatoes in a five pound sack.”

The barrier maintenance team takes great pride in the work they do to ensure the BAK-12/14 is always ready to save an aircraft, and a pilot, from catastrophe. Their squadron truly “leads the way.”