Nineteen Airmen died and hundreds were injured in the terrorist attack June 25, 1996, at Khobar Towers in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. At the time, it was the worst terrorist attack against the American military since the bombing of a Marine Corps barracks in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1983.

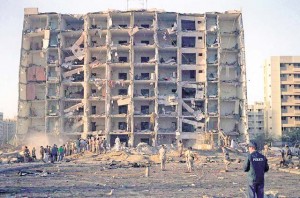

TYNDALL AIR FORCE BASE, Fla. (AFNS) — On the night of June 25, 1996, near Dhahran Air Base, Saudi Arabia, terrorists positioned a tanker truck filled with explosives less than 100 feet away from a building in the Khobar Towers complex that housed deployed Airmen. Shortly before 10 p.m. local time, the bomb detonated, killing 19 Airmen and wounding an estimated 400 others.

Defense Special Weapons Agency experts later estimated the bomb’s explosive power as equivalent to 23,000 pounds of TNT.

The terrorists had backed the truck into a parking lot directly in front of building 131, just beyond the fence, wire and concrete barriers surrounding the Khobar complex. The explosion left a crater 16-feet deep and 55-feet wide and completely sheared off the front half of building 131. The adjacent building, 133, was also hit hard.

“We had about 160 civil engineers living in building 133, all members of the 4404th Civil Engineer Squadron,” said Jimmy Prater, who was deployed from Mountain Home Air Base, Idaho as an explosive ordnance disposal technician at the time. “For the most part we were able to save everyone in 133, but we did lose one (civil engineer).”

Of the 19 people killed that day, Airman 1st Class Christopher Lester was the only one who resided in building 133. He had deployed from Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, as a power production technician. According to medical reports, Lester was killed by a large piece of glass that pierced his chest. Most of the Airmen died of blunt force trauma or injuries from glass.

“I was a staff sergeant at the time,” said Prater, now retired and working as the EOD contingency training manager at the Air Force Civil Engineer Center at Tyndall AFB, Fla. “My 90-day rotation was up, and I was due to leave on the ‘rotator’ flight in two days. I was in my room, lying down in bed when the door blew off and into me. When it did, it forced my feet upward so that my toes were touching my shins. As bad as it was, the solidwooden door actually saved me.

“After I pushed the door off me, I administered self-aid buddy care,” Prater said. “I popped my kneecaps out of socket, reset my ankles, put my kneecaps back and quickly put my boots on and went out to help. Me and a couple of other guys found a young lieutenant badly injured and bleeding. We tore two sheets into strips to bandage him together, ripped a door off its hinges and carried him down six flights of stairs.”

The young lieutenant was Michael Harner from Whiteman AFB, Mo., who was only six days into his first deployment. “I had been outside running,” said Harner, now a lieutenant colonel, and on his fourth deployment as the commander of the 577th Expeditionary Prime BEEF Squadron in Afghanistan. “I went up to the room and was out on the little balcony stretching when I actually saw the truck and the chase car drive by and the truck park. I was an eyewitness in the later investigation. I thought it was a little odd, but … I was a first lieutenant on a first deployment and it was my first time in the Middle East.”

Harner said he went back into the room, sat on the floor and stretched while he debated whether to call security. “I didn’t have much time though. About 30 seconds later I saw a flash through a small opening in the curtains,” he said. “I knew instinctively what had happened. I covered my eyes with my arm and rolled to my left just before the whole glass door exploded. My face was cut but my eyes weren’t hurt. I wrapped T-shirts around my head and leg and tried to find my way out in the dark but couldn’t, so I just sat back down and waited and prayed.”

Harner said he’s convinced the only thing that saved him was that he’d closed the doors and curtains. The Khobar Towers bombing was the catalyst for important changes that directly affect how civil engineers build and maintain the facilities that Airmen live and work in today.

Finding number one in the report by the Downing Commission, established in the aftermath of the bombing was, “There are no published (Department of Defense) physical security standards for force protection of fixed facilities.”

This finding led directly to the application of minimum antiterrorism construction standards for all occupied DOD facilities, said Jeff Nielsen, the antiterrorism-force protection subject matter expert at the AFCEC. Analysis of the Khobar Tower bombing indicated the need for progressive collapse protection, building standoff, glass fragment protection and mass notification systems, all features that are now included with Unified Facility Criteria 4-010-01, DOD Minimum Antiterrorism Standards for Buildings.

“I had a couple of more surgeries,” Harner said. “My right side ate the glass and my leg was pretty badly injured. I was on crutches for a month and had a lot of physical therapy. But in four months I was up and walking, then running. I have a lot of scars and I don’t have feeling in part of my leg, and every now and then a piece of glass will still work its way out of my skull.”

Prater said he and a security forces Airman did a security survey around the crater and parking lot and started doing post-blast analysis before going to the hospital to help wash and stitch the wounded. Prater himself would eventually have to have a total of eight hours of surgery, leaving him with scars along his legs and ankles that “still don’t work right.”

The terrorist bombing left behind more than just physical scars. “I knew something wasn’t right when I came back,” Harner said. “I woke up in cold sweats and had nightmares. They didn’t have a term for (post-traumatic stress disorder) when I went through it. I have moved past the PTSD now. I got through it by having a supportive wife, family and pastor, and by talking about it. I’ve spoken to people around the world — at churches, colleges and bases and, most recently, to 183 (civil engineers) at combat skills training before I deployed.”

For Harner, if he bumps his head in just the right place where scar tissue still covers a piece of glass, the night of June 25, 1996, immediately comes back to him. For Prater, recall is usually triggered by smell.

“To this day I go right back if I smell the same explosive compound,” Prater said. “Being EOD, I knew what is was immediately. When this happened to us, there weren’t any programs like they have now for PTSD or traumatic brain injury.

Around my 20-year mark, just when I was coming back from Iraq, my ninth deployment since Khobar, PTSD began being recognized and I was able to get some help. We’ve come a long way with this.”

Author’s note: June 25 is the anniversary of the terrorist attack on Khobar Towers and June is National PTSD Awareness Month. Visit the Veteran’s Affairs website at http://www.ptsd.va.gov/index.asp for more information on PTSD and resources available to help.