The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency has been searching for remains of U.S. military members in 45 nations.

Besides bringing closure to their loved ones, this effort has strengthened America’s diplomatic ties with those nations, said the agency’s director, Kelly McKeague, who spoke virtually today with the Center for a New American Security.

The Defense Department partners with the State Department in this effort, as well as the local population of each country, he said.

When the agency sends investigative or recovery teams to those nations, local residents are usually employed to assist, McKeague said.

“Villagers from far and wide descend upon the site and help the team with the labor that’s associated with that particular excavation,” he said. “We are projecting American values in a positive way. And more importantly, for many of these cultures and many of these citizens, it’s an opportunity to give back.”

McKeague provided three examples.

In the South Pacific islands of Papua New Guinea, Palau and the Solomons, they revere ancestors who have passed away.

“When they hear of our teams coming into their village to look for what they call ‘our grandfathers,’ it’s an amazing dynamic. Some of our team leaders who are captains and master sergeants are made tribal chiefs, which I think is an incredible dynamic in that people-to-people contact. … It’s also a means of projecting soft power in terms of American values at the local and regional level,” he said.

In 1985, just 10 years after the last U.S. servicemember left South Vietnam, the government of Vietnam approached the United States and said that they wanted to cooperate with the United States, because they knew that finding missing Americans is important to us, McKeague said.

That conversation took place amid economic sanctions and trade embargoes with Vietnam, and predated normalization of relations 10 years later, he noted.

Today, Vietnam is a prosperous, stable country, due in part because they manifested their trust in the U.S. by unconditionally cooperating in the recovery of MIA remains.

Vietnam’s expertise in recovering remains is outstanding, McKeague said. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when agency personnel could not travel, Vietnam’s teams unilaterally excavated remains of U.S. service members.

One of those remains identified was Navy Cdr. Paul Charvet, an A-1H Skyraider pilot shot down over North Vietnam on March 21, 1967.

About two years ago, the agency received those remains from Vietnam and identified him. His mother, then 101 years old, was on hand to receive the news that her son had been found, he said.

“What an incredible moment that was, made possible because the American-trained Vietnamese recovered those remains that we then identified,” he said.

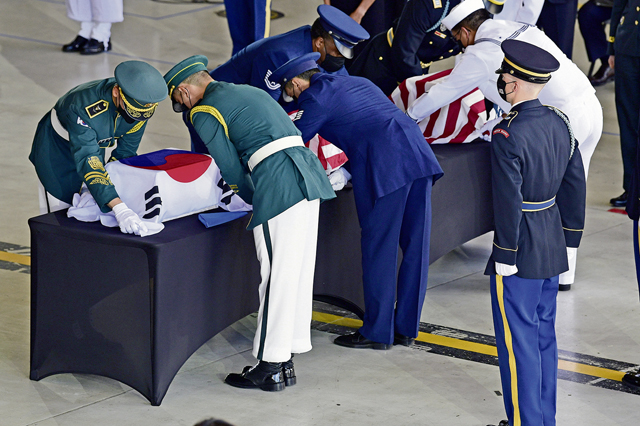

South Korea, another big success story, approached the United States about 20 years ago and said that they still had about 300,000 people missing from the Korean War, and they asked for help from the U.S., McKeague said.

The agency helped South Korea set up a similar agency. “Their laboratory rivals ours in terms of expertise. We have had joint scientific exchanges. We’ve had joint operations,” he said.

McKeague said his greatest wish is that North Korea will resume repatriation of remains of U.S. service members.

“North Korea presents a great opportunity … that might one day lead to better relations,” he said.