A team of military and civilian researchers has identified a new sleep disorder that’s been disrupting the lives of trauma survivors for decades, if not centuries.

The Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine published the groundbreaking study, titled “Clinical and polysomnographic features of trauma associated sleep disorder,” on its site in August.

While there have been related studies, this was the largest to date and identifies trauma associated sleep disorder, or TSD, as a distinct sleep-related disorder or parasomnia, explained U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. (Dr.) Matthew Brock, the study’s lead author and chief of the San Antonio Market Sleep Disorders Center at Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, Texas. “We believe trauma-associated sleep disorder is the first adult sleep disorder and rapid eye movement (REM) parasomnia identified since Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD) was identified more than 35 years ago,” he said.

Dream enactment

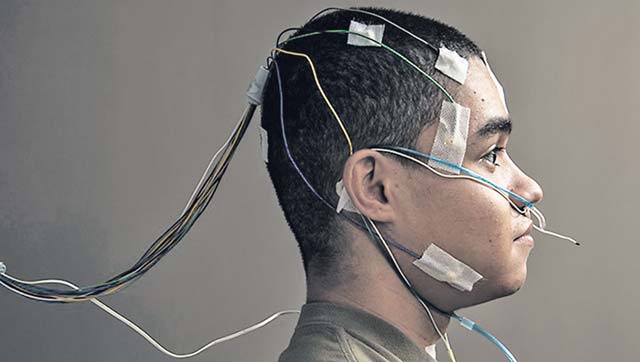

The study, which spanned five years, included 40 service members who had experienced trauma, mainly from combat, and were experiencing dream enactment. That is when someone acts out dreams physically or verbally. The study comprised a clinical interview and video-recorded sleep study. “We watched all eight hours of video on each sleep study, which is not typical,” Brock said, noting that many sleep centers record eight hours but rarely watch the video recording in its entirety.

“Our key finding was that most of these patients had parasomnia behavior, or movements and vocalizations in REM sleep. This is groundbreaking because traditional wisdom is that parasomnia behavior is almost never captured in the sleep lab but is frequently cited by patients as a symptom they’re experiencing at home.”

Typically, during REM sleep, the skeletal muscle, other than eyes, diaphragm and sphincter muscles, is paralyzed to prevent people from acting out dreams. However, in some cases, the part of the brainstem responsible for paralyzing the skeletal muscle degenerates, which may result in dream enactment. This is called RBD and is commonly seen in people with neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, Brock explained.

“Dream enactment behavior can include punching, kicking, defensive posturing, yelling, and movements,” Brock said. “This is disruptive, and often scary, not only for the patient, but for his or her bed partner as well.”

TSD is similar to RBD regarding dream enactment. However, TSD also includes vivid, repeating nightmares about the individual’s trauma and symptoms of autonomic hyperarousal, which is when the fight or flight response kicks in and one’s heart rate or respiratory rate accelerates during sleep.

Distinguishing TSD from other sleep disorders

A key focus of the study is to distinguish TSD from other diagnoses, such as RBD, post-traumatic stress disorder and nightmare disorder, Brock said.

For example, TSD symptoms are often associated with PTSD. However, PTSD includes daytime and nocturnal symptoms, while many TSD patients only experience nocturnal symptoms.

Additionally, nightmare disorders typically don’t include dream enactment or repeating nightmares about a trauma experience, Brock explained.

TSD symptoms and history

Although it had not been given a name, TSD symptoms have been studied for many years. Retired U.S. Army Col. (Dr.) Vincent Mysliwiec, director of sleep medicine, UT Health San Antonio, and co-author on the study, has been researching this phenomenon since 2003, when he was assigned to Madigan Army Medical Center and during the peak of Operations Iraqi and Enduring Freedom.

“This was when we initially saw active-duty service members who presented with trauma-related nightmares, dream enactment behaviors, and rapid breathing, night sweats and racing heart rates shortly after returning from combat,” Mysliwiec said.

“We evaluated many service members who had these symptoms but did not meet diagnostic criteria for either REM sleep behavior disorder or PTSD,” he added. “It was unknown at that time what diagnosis they had.”

By having TSD officially recognized as a distinct, novel parasomnia, “we are hoping to encourage future research into the disorder as well as treatment-related studies,” said Mysliwiec, noting that would best be accomplished by larger studies at both military and veteran health care facilities. Additional research also would be beneficial for people with non-combat-related trauma. “Evaluating and studying TSD in the civilian population would help provide an enhanced understanding of this disorder,” Mysliwiec said.

The goal is to have better awareness and treatment to help improve trauma survivors’ quality of life, Brock said. “People who suffer from TSD are not getting quality sleep and their bed partner is not getting quality sleep,” he said. “Many are afraid to go to sleep. They’re having to go back to battle or trauma at night in their sleep, then, during the day, dealing with a lack of quality sleep. Each morning is like the morning after they experienced the trauma, but for them, it’s every day. My greatest hope is that we can help make a positive impact for anyone suffering from TSD.”