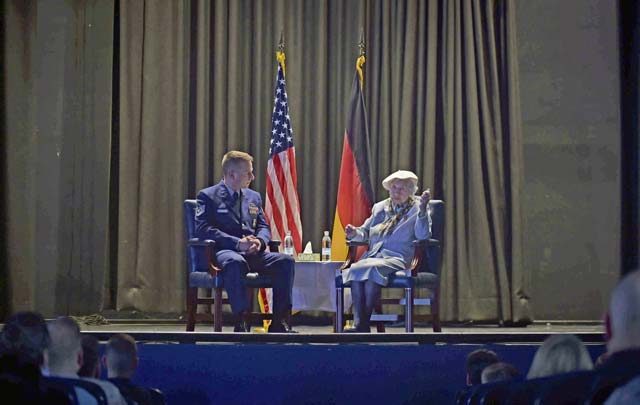

Selma van de Perre, 92-year-old Holocaust survivor, sits with Tech. Sgt. Robert Jarvis, 86th Civil Engineer Squadron firefighter, during a Holocaust remembrance event May 6 on Ramstein. Van de Perre shared her story of surviving Ravensbrueck, a womens concentration camp.

Selma van de Perre was just a young woman when World War II broke out in Europe. She remembers the day when her older brother came home with the news.

“He came home on the 10th of May shouting, ‘Wake up, wake up! It’s war, it’s war!’” she remembered.

Van de Perre shared her story of survival in front of a packed crowd May 6 at Hercules Theater on Ramstein.

“In 1941, they started collecting Jews,” van de Perre said. “In 1942, they started calling out Jewish boys and girls as well as taking them from the street. They had big vans and they just collected (from) the street daily.”

Van de Perre and her family were of Jewish descent, meaning they were a target in 1940s Europe. As persecution against the Jews increased, van de Perre knew it was no longer safe for them to stay where they were.

As others were being imprisoned, hauled off to concentration camps and even killed, van de Perre arranged for her family to be taken into hiding in the south of Holland, and eventually met a group of doctors who happened to be members of the resistance. After spending time with many members of the resistance, she made a decision to stand up, she joined the fight against Nazi tyranny.

Van de Perre explained that they were short of people helping the resistance because so many of them were already being imprisoned or had to go into hiding themselves.

“So I said, ‘Can I help?’” she explained as she remembered how enthusiastic she was as a young girl. “They said, ‘Oh yes, are you sure?’ and I said yes. So that’s how my career started.”

She found herself delivering what she called “illegal papers” for the resistance around Holland and in other European countries. She also transported money used for the cause and also to pay families which housed Jews hiding from persecution.

“I was given a few assignments,” said van de Perre, “All of them were quite dangerous and very risky.”

Along the way, the resistance gave van de Perre a new identity.

The Nazis however eventually caught van de Perre. She was brought to the police station where she was interrogated for several days before being sent to a concentration camp in the Netherlands.

“I was told I was (going to be) in prison for the duration of the war,” she said. “I was put to work in the gas mask factory.”

Van de Perre did not stop resisting the Nazis even while she was imprisoned. When they put her to work, she made some of her work unproductive. Van de Perre said she intentionally assembled the masks in such a way that they would come loose by the time they would be used.

Later on, she and other prisoners were moved to the Ravensbrueck womens’ concentration camp in Germany, where she and her fellow prisoners were subject to cruelty and physical abuse.

“I saw the most terrible things happening there,” van de Perre said.

She recalled a story of when two so-called nurses came to assist a very sick woman and just took her mattress and threw it on the ground with her on it and just dragged her outside as she screamed and cried out.

“The woman was screaming, ‘No, no, no, please, no, no, no!’” van de Perre recounted. “We never saw her again.”

Van de Perre herself was also abused and degraded by the Nazis at Ravensbrueck. One day she missed a roll call because she was unable to move, and she remembers being beat with a belt until she fainted.

In addition to being beaten and tortured, van de Perre and her fellow prisoners were also subjected to starvation. Van de Perre said they were not given lunch despite working for so many hours and not being paid. After a long day of work the prisoners would be given a slice of bread and so-called coffee.

“Sometimes there was soup — it was called soup, but it was just water with grass in it. And that was all you had, so people became very thin quite quickly,” she explained. “Some prisoners even died of starvation at the camp.”

As the war raged on, the Nazis began killing off more prisoners at Ravensbrueck.

Women who were disabled or impaired started being singled out and put into groups, said van de Perre. The Nazis told them that these women did not have to work anymore; they were gassed.

One day rumors began spreading around the camp that they were going to be freed. At first, van de Perre said they did not believe the news.

Later on however, someone arrived to assure them that the war was over and they indeed were free.

“After hours of waiting, there was a little sports car arriving with this very nice tall, blonde Swedish man in it. He told us that he was… a friend of the head of the Swedish Red Cross.”

The prisoners waited for hours to be picked up. As the day turned to night, the man offered van de Perre a cigarette. As the Swede lit the cigarette for her, someone from the camp shouted at van de Perre not to smoke. But her new Swedish friend assured her that she could smoke and the Nazis had no more authority over her.

“It was then I suddenly felt I was free,” she said with a smile of relief.

Van de Perre survived approximately one year at Ravensbrueck, enduring the cruel and degrading treatment of the Nazis. She said what kept her going was the will to live and the mutual support of her fellow prisoners who became her friends.

“I didn’t want the Germans to be successful in having me dead,” she said. “I was (in) very bad (condition) at times, but I survived.”

Van de Perre said she considers it very important her and other holocaust survivors to speak out and tell their story to the coming generations.

“I speak to students so they can pass it along to their children, because I think it’s very, very important that our stories are getting through in the future so that it won’t happen (again),” she said.

After van de Perre concluded her talk, Col. Brandon R. Hileman, 86th Airlift Wing vice commander, thanked her and presented her with a gift as a token of appreciation.

“As today’s event comes to a close, we’d like to thank Ms. Van De Perre again for joining us. It’s been a pleasure ma’am,” Hileman said. “May each of us remember the powerful story we heard here today and use the knowledge to fight the evil that exists in our society, to stand up for freedom, equality, justice and peace and to better ourselves and the world around us.”