Capt. Genesis Guerrero, a chaplain for the 39th Air Base Wing, was 17 years old when his family almost fell apart.

It started with an ugly discovery, then escalated into fits of rage as he witnessed his parents arguing hysterically: his father, Gene, had been caught being unfaithful.

“I walked out of my room to make sure it didn’t escalate to violence because dad had a history of hitting mom whenever he was angry,” Guerrero said.

“They continued to argue in front of my sister and I,” he recalled. “Mom was broken and angry, and dad — who I had never seen cry up to this point — was crying and seemed so lost.”

Guerrero recounted the scene as a whirlwind of arguments and expletives ascending further into chaos, culminating into unexpected terror — Gene picked up his sawed-off shotgun and pointed it at his head, preparing to shoot himself and end it all.

The two siblings pleaded with their father not to pull the trigger, while their fearful mother sat frozen.

“He didn’t want to kill himself in front of us, so he grabbed the keys to his red Chevy Blazer, gun in hand, and said we would never see him again,” Guerrero continued. “As he climbed into his truck, we began to cry with even more desperation. I tried to pry the driver’s side door open, but he locked it with his windows sealed shut.”

The teenager’s mind raced. He frantically ran back into the house and grabbed the first thing he saw: his homecoming portrait. Then he dashed outside just in time to catch his father shifting the truck’s gear into reverse. He pleaded with his father through the driver-side window, telling him how much he loved him and needed him.

“I cried in anguish,” Guerrero recalled. “I pointed at the picture and told him to think about his family before he killed himself. At that point he opened the door, took the picture and left. I watched him drive away not knowing if I would ever see him again.”

“I went back into the house and sobbed uncontrollably with my mom and sister until we couldn’t cry anymore,” the chaplain added.

For Guerrero, the events of that day served as a climax in a long and painful chain of events which began early in his life.

His family hailed from the U.S. territory of Guam, a small island in the Pacific Ocean. However, due to his father mingling with the wrong crowd and getting into trouble, the Guerreros fled more than 1,000 miles away to the Philippines. After two weeks in the tropical republic, the parents decided to send their two children out even further — across the ocean to the continental U.S. to live with relatives, hoping their offspring could find a brighter future.

Guerrero said he felt safe, but overwhelmingly alone during his life in exile; he found himself in a new world, immersed in an unfamiliar culture and living with people he barely knew.

“My sister and I lived without our parents in Colorado for about two years,” said Guerrero. “There were many nights I cried myself to sleep, not knowing if I would ever see my parents again because I struggled with the possibility that dad could go to jail, or even worse … get murdered.”

There was no one to ease those fears, Guerrero recalled, saying although he and his sister were in a safe environment, they felt like strangers in their new home.

He described his relatives as “nice people,” but added, he couldn’t help but feel like a “stepchild” and an “irritating house guest.”

“They didn’t sign up to raise four kids, two of which were not their own,” he said.

Guerrero’s mother eventually made her way to the U.S. without her husband. She moved with her children to a rural town in Georgia where close to a year later, Gene arrived to reunite with the family.

Guerrero remembered his father being met with a mixed reception.

“I was always told I was a happy-go-lucky kid, so I received dad with open arms,” he said. “My sister had the most difficult time forgiving dad, but mom was relieved because she finally had her husband back to help shoulder burdens.”

Once reunited, Guerrero remembered the rocky family dynamic as mostly good until that harrowing night when his father stormed off with his shotgun, threatening to kill himself.

Guerrero said he didn’t remember much of what happened the rest of the day, only that he came to grips with the reality his father will make his own decision.

Thankfully, after hours of terrified waiting, Gene returned home safely.

When Guerrero asked his father what changed his mind about ending his life, the homecoming portrait was the answer.

Looking at that photograph helped Gene see the bigger picture.

“It helped him think of his family,” said Guerrero. “The picture served as a change in perspective.”

But it wasn’t just his dad who had to change, because the younger Guerrero explained he also needed a new perspective — and a change of heart as well. He harbored bitterness because his father’s troubled lifestyle sent the whole family into exile.

It was not until Guerrero said he discovered his faith at the age of 18 when he began yet another difficult journey: the path to healing.

He described forgiveness as the first step to healing, and the most challenging one as well.

“I blamed my dad for everything at one point,” he said. “Dad’s immaturity and poor decisions moved us halfway around the world and left us struggling to make ends meet. We went from having everything we wanted and needed in Guam to living in low-income housing in south Georgia.”

Guerrero didn’t want to forgive his dad, but was encouraged by a close friend of his who reminded him about one of the principles of his newfound Christian faith: forgive because you have been forgiven.

And so he made an effort to reconcile with his dad, adding it was a long process with many obstacles. But as he continued working through this relationship, he found even at the end of a painful history, one could start a new and hopeful chapter.

“I got a chance to develop a good relationship with my dad,” Guerrero said. “We got a chance to talk about a lot of things. It was cool just to have a man-to-man conversation with him, and to hear his heart behind it all.”

This reconciliation between father and son manifested in one of the most poignant ways: on Guerrero’ wedding day, when Gene served as one of his son’s best men.

“I had two best men at my wedding: my dad, and my best friend who helped me forgive my dad,” said Guerrero. “It was such a privilege to have both my biological and spiritual fathers to encourage me on such an important day in my life.”

It was the process of grace, faith, forgiveness and reconciliation which Guerrero said helped him in the journey to healing. It helped him rebuild his relationship with his father and find peace within himself.

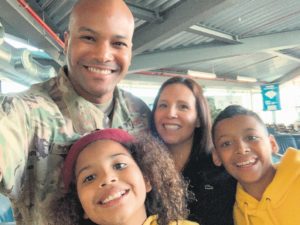

Now, as a chaplain in the U.S. Air Force, he strives to help Airmen find inner peace as well.

“In order to truly have peace in your heart, you have to be willing to forgive,” he said. “Until then you are suffering in silence.”

Guerrero added along with forgiveness, a change of perspective is also needed to guide people along in their process of finding peace.

To illustrate his point, he described a cross: once instrument of death and torment in ancient times, it now symbolizes hope and healing for billions of people around the world—both religious and not.

“For me, that’s what faith can offer,” the chaplain said. “It gives you a different lens through which to look at life: a lens of hope that shows me no matter what my circumstances are, they don’t define me.”

Gene Guerrero eventually passed away in 2012 due to natural causes. Guerrero expressed how grateful he was for the opportunities to spend time with his father before saying goodbye for the last time. Although they stumbled on a broken road in separate journeys, he concluded they both saw life through a new lens … and gazed upon a bigger picture which saved their lives.

“Since then, I’ve been able to look back and slowly connect the dots that seemed so fuzzy at one point,” he said. “And now I want to help people see all of life, both the tragedies and triumphs. For me this begins with serving my wife, four children and the Airmen my God has entrusted me to care for.”