The water was ice cold with rough, choppy waves crashing on the beach. The early morning moon shed just enough light for thousands of men to hide in the cover of darkness. Many of the men — some hardened veterans, some barely 18 years old — silently prayed while they awaited the order to begin Operation Overlord.

Operation Overlord, more commonly known as D-Day, was the largest land, sea and airborne invasion in history. More than 156,000 service members braved the frigid waters and hostile airspace to storm the beaches of Normandy, France, June 6, 1944.

“I couldn’t see anything because I was hunkered down in the boat as we went in, but I do remember seeing the looks on the faces of the young men,” said U.S. Army Pfc. Jesse A. Beazley, 38th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division combat rifleman. “We had kidded in life like Soldiers do, but all at once it got completely silent. I thought of my home, my mom, my dog and my friends. I wondered how in the world I came to be here in this situation: a young man, realizing that probably I didn’t have much chance to live because I knew what was ahead of us.”

The invasion lasted until June 24, and is considered to be the turning point of World War II. The successful invasion meant the Allied powers could finally gain control and begin the end of the war. However, the success of Operation Overlord depended heavily on months of planning and behind the scenes work.

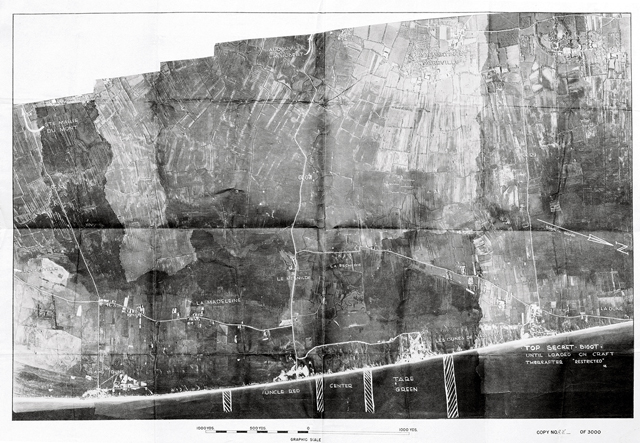

Enter the 33rd Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron, known today as the 24th Intelligence Squadron at Ramstein Air Base. While members of the U.S. Army Air Corps were limited to the technology of the time, they played a vital role in informing military leaders as the invasion was planned.

How many people are there? What kinds of equipment do they have? How far away are they? What can Allied warfighters expect when they get there? The answers to these questions were essential to advancing Allied forces and minimizing the loss of life.

The 33rd PRS was able to answer these questions by sending photographers into the Axis powers’ airspace, usually in unarmed aircraft or aircraft ill equipped for air-to-air combat, to take pictures of the war zone.

“They were flying in contested airspace unable to defend themselves to get some pictures and hopefully get back to give them to analysts,” said U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. Jacob Scott, 24th IS unit deployment manager. “Over time we became more efficient by putting the equipment into the belly of the plane, but we started basically as just a guy looking out a window and taking pictures with a camera.”

Though the idea of collecting information about opposing forces is not a new military strategy, the way the information was collected has changed with the advancements of technology. The U-2 Dragon Lady, a high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, completed its first test flight just 10 years after the end of World War II.

Other intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance platforms and sensors over the years include the RQ-4 Global Hawk, MQ-1 Predator, and MQ-9 Reaper remotely piloted aircraft.

“Prior to about three years ago everyone focused on their own mission, and we did our mission [independently],” Scott said. “I guarantee there was overlap. When we started to modernize and created the Air Force Distributed Common Ground System, we became what we call sensor agnostic. We will use anything we have available to us to answer requests for information, fill in the gaps, and confirm our calls.”

The Air Force Distributed Common Ground System is the Air Force’s primary ISR planning and direction, collection, processing and exploitation, analysis and dissemination weapon system. The weapon system employs a global communications architecture connecting multiple intelligence platforms and sensors.

As time went on and ISR technology advanced, the adversaries the U.S. focused on shifted from sovereign states to the Global War on Terrorism. Scott mentioned many ISR specialists at the time were more experienced with conventional military concepts rather than the guerrilla warfare tactics being used when he enlisted in the Air Force.

“My generation went through counterinsurgency and the Global War on Terror and we adapted to that,” Scott said. “Now, as we transition out of the Global War on Terror and into looking at our near-peer adversaries we are back to uniformed personnel, aircraft, tanks and things like that. My Airmen and young staff sergeants — the ones that are doing the mission day in and day out — are now the experts.”

Scott emphasized the importance of knowing the roots of the squadron. He encourages ISR Airmen not to get discouraged although many of the mission-centric wins may not be able to be shared with friends and family.

Many believe history repeats itself. Whether providing aerial photographs of Normandy or analyzing information collected from modern-day ISR platforms, the 24th IS continues to accelerate change and shape the information space across Europe and Africa, while playing a critical role in the Department of Defense’s mission — no matter the adversary.

Editor’s note: U.S. Army Pfc. Jesse A. Beazley’s quote originated from an interview for the Veterans History Project for the Library of Congress.